[Download the full article (PDF) via ‘Download Publicatie’]

About Sergei Magnitsky, the fight against impunity and Pieter Omtzigt’s role in it.

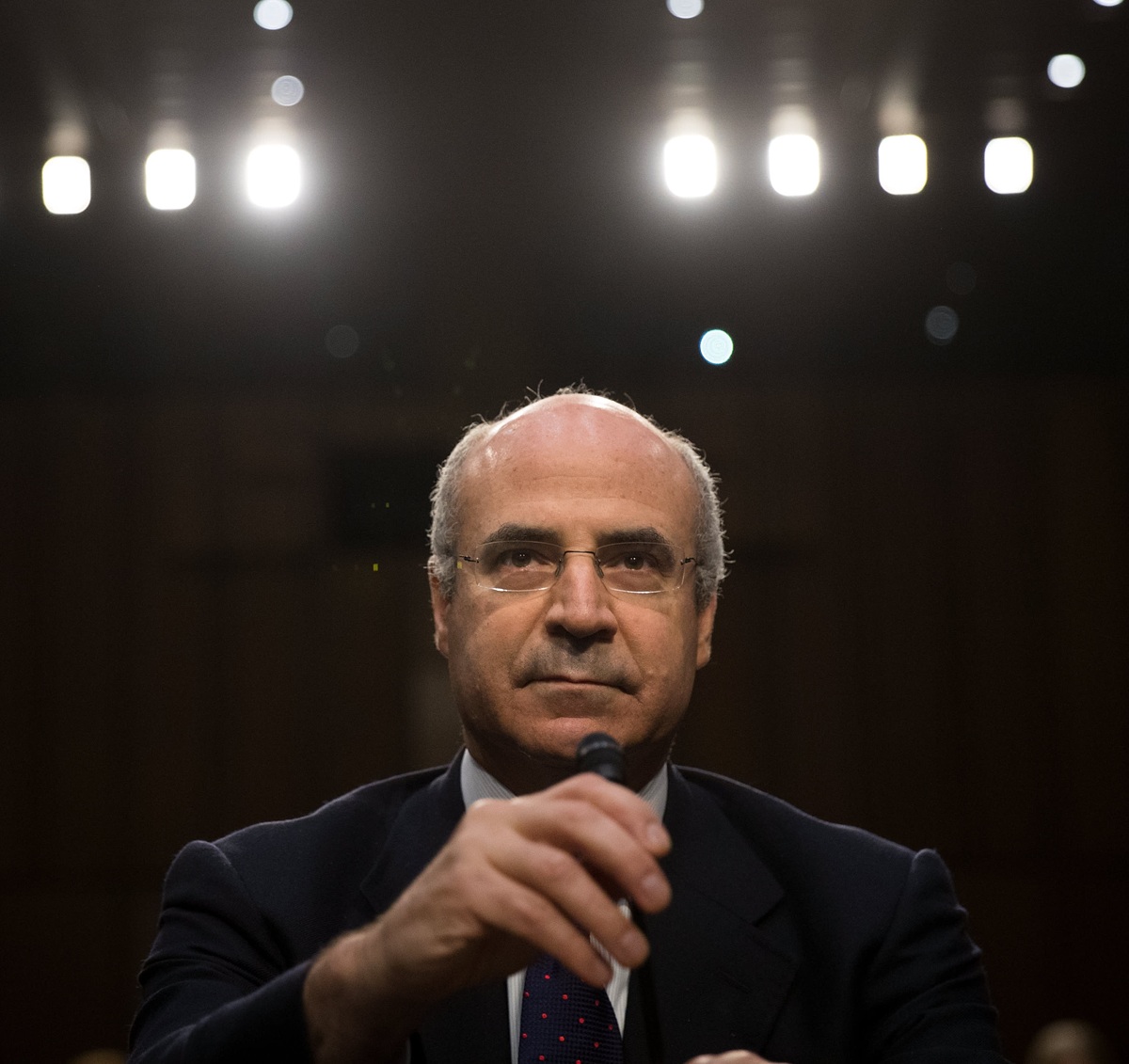

When Bill Browder embarked on a career as an investor in the 1990s, no one could have imagined he would one day become a human rights activist. Yet that’s precisely the path he took after the death of Sergei Magnitsky, the Russian lawyer who died in a Moscow prison in 2009 after being tortured by authorities. “The odds of a hedge fund manager becoming a human rights activist are almost zero,” says Browder. “But after Sergei’s death, I felt a moral obligation to put everything aside and fight for justice.”

On October 8, 2025, Browder will be one of the keynote speakers at the symposium organized by the NSC and the Scientific Bureau of New Social Contract (WB-NSC) in Scheveningen, highlighting Pieter Omtzigt’s twenty years of work at the Council of Europe. The interview with Bill Browder reveals how a personal tragedy led to an international campaign for justice and how Pieter Omtzigt became a key figure in the European fight against impunity.

Turning point: Sergei Magnitsky’s murder

Browder recounts how he was hounded for years by Russian authorities for his efforts to expose corruption. Unable to catch him in London, they went after his associates in Moscow.

Sergei Magnitsky , a 36-year-old lawyer who had exposed fraud by Russian officials, was arrested and tortured. When he refused to retract his statement and falsely accuse Browder, he was beaten to death in his cell by eight guards in November 2009.

“It was the most evil thing I’ve ever witnessed,” says Browder. “I wasn’t the one who did this to him, but without our cooperation, he wouldn’t be in that position. That sense of guilt and responsibility was so overwhelming that I decided to dedicate my entire life to justice for Sergei.”

From businessman to activist without a manual

Browder had no legal or activist background. Yet, that proved to be an advantage. “I had no orthodoxy to adhere to,” he explains. “My only goal was justice. If there wasn’t a law that made it possible, I had to figure out a mechanism myself.”

When he delved into international legal remedies, he discovered there was nothing applicable: no international court, no treaty basis, no instrument whatsoever to punish the perpetrators. “If I had been a lawyer, I probably would have concluded it was legally impossible,” he says. “But I wasn’t a lawyer; I could think outside the box.” It was precisely for this reason that he decided that if there was no law, he had to create one.

That mechanism became the Magnitsky Act : a law that targets foreign human rights violators by freezing their assets and restricting their freedom of travel. “These people are killing for money,” says Browder. “Their vulnerability is their wealth and their access to the West. That’s where I had to hit them.”

The American Beginning

Browder found a sympathetic ear with two U.S. senators: Democrat Benjamin Cardin and Republican John McCain. They not only listened to his story but were also personally touched by the simplicity and moral urgency of his proposal. In 2012, the Senate voted 92-4 in favor of the Magnitsky Act ; in the House of Representatives, there was 89 percent support. President Obama signed the act into law on December 14, 2012.

“It was a turning point,” says Browder. “Suddenly, there was a concrete legal instrument that held individuals accountable for gross human rights violations. It gave hope to victims worldwide.” The US law was initially limited to Russia, but quickly became a model that was also adopted elsewhere.

Canada followed suit in 2017 with its own Magnitsky Act, followed by the United Kingdom in 2018. “Canada was crucial,” says Browder. “Nobody is anti-Canadian, so a Canadian law had enormous moral impact.” Yet the biggest goal remained: Europe.

Europe: The long road to a Magnitsky Act

While the US acted relatively quickly, Browder encountered skepticism in Europe. Member states pointed fingers at each other or the European Commission. “Everyone hoped I would give up, because almost no one believed something like that was possible in the EU,” he says.

A turning point came in 2013 at the launch of Browder’s book, Red Notice, in the Netherlands, a year after the American law. Pieter Omtzigt played an active role in this event, along with other parliamentarians. “That meeting was more than a book launch,” says Browder. “It brought together politicians, journalists, and activists and gave a European face to the Magnitsky movement.” Some of those involved later disappeared, but Omtzigt remained. “He was one of the few who has provided unwavering support since then. That made him an indispensable ally.”

From The Hague to Brussels

The campaign to introduce the legislation in the Netherlands wasn’t immediately met with enthusiasm by the Dutch government. Pieter Omtzigt then devised a clever workaround: a motion in the House of Representatives instructing the government to advocate for a European Magnitsky Act, and failing that, to draft a Dutch version itself. In 2018, the House adopted this proposal, supported by a broad coalition of parties. “It left The Hague with no choice: either take it seriously in Brussels, or enact a national law,” said Browder .

But Brussels was a different story. The European Commission and the Council cynically referred to each other: the Commission believed the matter was the responsibility of the member states, while the member states pointed to the Commission. “Everyone was trying to let the issue die a death knell,” says Browder. “They were afraid of losing their lucrative ties with Moscow.”

Ultimately, more and more countries rallied around the Dutch proposal—Sweden, France, and others—often not out of enthusiasm, but because they preferred to ride the wave rather than draft their own national legislation. Yet, Hungary under Viktor Orbán remained unruly. Because European sanctions legislation requires unanimity, this seemed like a definitive blockade.

Browder again enlisted American allies. Senator Roger Wicker , a Republican from Mississippi, called the Hungarian ambassador in Washington with a stern message: if Budapest didn’t withdraw its veto, he would publicly confront Orbán. Within a day, Hungary changed its mind. “It was pure geopolitics,” says Browder. “Orbán wanted to maintain good relations with the Republicans in Washington at all costs.”

The outrage at Alexei Navalny’s poisoning, actually proved the final push to get a sanctions regime. It’s not formally called the Magnitsky Act —a concession to Hungary—and corruption wasn’t included as a criterion. But the principle was broken. “Without Pieter Omtzigt, that would never have happened,” concludes Browder. “He connected national politics with European dynamism and kept the fire burning when everyone thought it was impossible.”

Enemies and personal risks

Browder’s work, however, did not go unnoticed in Moscow. In 2013, Russia organized a posthumous trial against Magnitsky and sentenced Browder in absentia to years in prison. Through Interpol, the Kremlin tried several times to have him arrested. He was temporarily detained in Madrid and Geneva and has lived with constant threats ever since.

“I’ve been threatened with kidnapping and murder,” he says. “Traveling remains dangerous. Even in the West, I have to be vigilant. But I have no choice – the fight for justice must continue.”

Critical look at the EU

Although the EU has had its own sanctions regime since 2020, Browder is critical. “The European Magnitsky Act is subpar,” he says. “Corruption is excluded as a basis for sanctions, and to this day, the perpetrators of Sergei’s death have not been punished.”

He emphasizes that the fight is far from over. “It’s an ongoing campaign. Every time we pass a law, it has to be enforced. And that’s where the political will is often lacking.”

Inspiration and lesson

What can a Dutch reader learn from Browder’s story? First, that perseverance pays off. “Everyone said it was impossible,” he says. “But by being creative and finding allies, we managed to create a mechanism that has a global impact.”

Moreover, his collaboration with Pieter Omtzigt demonstrates how important individuals can be in politics. “Without Pieter, I probably would have given up on Europe. He devised new strategies and remained involved for years. That kind of leadership is rare.”

Conclusion: a battle that continues

Bill Browder is no longer the businessman he once was, but the driving force behind a global movement against impunity. His story shows how personal tragedy can lead to systemic change—if someone is willing to sacrifice everything for justice.

In October, he will speak in the Netherlands, along with Pieter Omtzigt, about the twenty years of struggle in and around the Council of Europe. It’s not just a retrospective, but also a call to action: the fight against corruption and human rights violations is never over.

“What drives me remains the same,” Browder concludes. “Sergei gave his life for the truth. My job is to make sure his death was not in vain.”